User stories are granular representations of people’s goals, aspirations, and expectations. Designers and product managers use them to gather an in-depth understanding of their users’ needs, empathize with them, and generate solutions that will provide value to the people they design for.

In today’s article, we’ll take a closer look at what user stories are, how we should go about creating them, and some essential criteria to validate them.

Let’s dive right in, shall we?

What are user stories?

User stories are a first-person representation of an individual’s needs. They describe what users aim to achieve by interacting with a particular product. They’re a valuable tool for development teams since it’s a source of empathy that enables them to better understand how a product fits in the end-user’s day-to-day life.

User stories typically consist of three essential components—the subject of the action, the action they want to perform, and the desired transformation:

As a <who?>, I want to <what?>, so that <why?>.

While this does appear as a very straightforward sentence, it does provide us with a wealth of insight about:

What are we looking to create;

Why we’re choosing to do so;

Whom it’s being created for;

By expanding on the desired transformation, a user story provides the whole team with important context on what the end-user’s goals are. As a result, this informs the functionality of a product and helps designers establish the order and the way features are designed.

Why you need them

There is a wide array of benefits to user stories; here are a few of them:

They provide teams with a clear overview of user needs in a digestible and straightforward manner. This enables them to collaborate and organize efficiently around clearly defined objectives;

User stories are extensions of user personas—they provide us with a wealth of insight into the people we’re designing for;

User stories are essential when it comes to preventing “feature creep”—a pervasive issue UX and UI designers have to deal with regularly. Working with stories helps keep the project within the initial scope;

They help keep products user-oriented. Stories act as a constant reminder of who this product is developed for, which allows creating products that are more thoughtful and user-focused;

User stories are a vital tool for collaboration since they act as a source of truth that informs a product’s development;

User stories in the grand scheme of things

Think of user stories as a scaffold. They’re there to give us a solid foundation and guide us in the right direction. Stories are especially important during project scoping, this is where they are generally outlined and refined.

They typically begin as a very broad and general theme and are narrowed and improved over time until they become granular enough to be actionable.

In terms of the product design process, user stories work best at the empathy stage of the design thinking framework.

Writing a good user story

Telling stories in an informative way may seem very simple, but there is a variety of guiding principles we need to take into account:

Users always come first—user stories should only be about…well, users. It’s essential to underline that the people tasked with writing them should have a solid understanding of the user personas and the research done to inform them;

Creating stories should be a collaborative effort. Since stories are a great way to calibrate a team’s cooperation, they must be developed collectively;

Stories should be short and sweet—they should be easy to understand, which is why it’s essential to ditch any confusing or ambiguous language;

Think about validation criteria—think about the conditions that a feature needs to satisfy in order to fulfill a user need;

Here are a few examples:

🛑 A poor example 1:

As an Instagram user, I want to share images, videos, and stories so that I can keep in touch with my friends.

❇️ A better example 1:

As a socially active person, I want to be able to share pictures of my life so I can update and stay in touch with my friends on life events.

🛑 A poor example 2:

As a website visitor, I want to see buttons react on hover, so I can see that they’re clickable or inactive.

❇️ A better example 2:

As a website visitor, I want to be able to find the listing I need quickly so that I don’t have to waste time browsing.

🛑 A poor example 3:

As a project manager, I want to be able to track an employee’s progress, so I can do my job better.

❇️ A better example 3:

As a project manager, I want to keep an eye on my teammates’ progress, so I can report on their work and offer help if necessary.

🛑 A poor example 4:

As a social media marketer, I want to see the number of likes a post amassed, so I can tell if I did a good job.

❇️ A better example 4:

As a social media marketer, I want to measure the engagement of my posts so that I can tell which posts do best and what kind of content people respond to.

🛑 A poor example 5:

As a product owner, I want to see my metrics so that I know if things are going well.

❇️ A better example 5:

As a product owner, I want to be able to quickly and easily see the key product metrics, so that I can assess the progress and spot any changes immediately.

To recap in a more convenient format:

Some great formulas

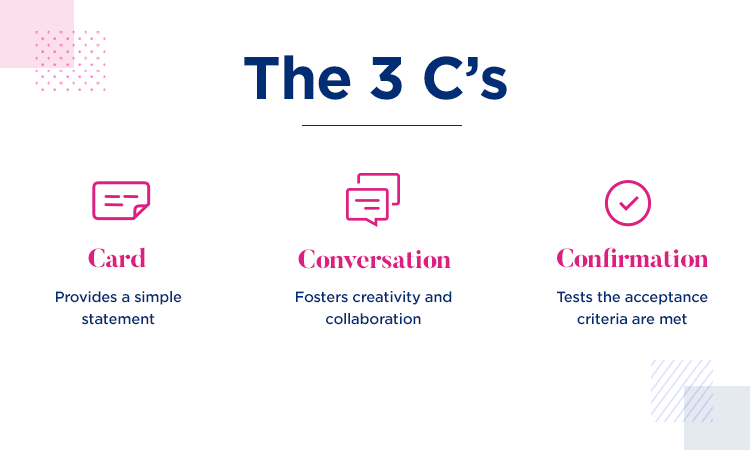

There are two important mnemonic formulas that enable us to write better user stories—the 3 C’s and INVEST. Let’s take a closer look at them.

3 C’s: card, conversation, and confirmation

The “3C” formula is a straightforward and self-explanatory instruction to how a user story should be approached.

A card is a piece of paper, a post-it note, or a digital representation of a story;

A conversation is an interaction that revolves around a “card’s” subject. It allows developers, designers, stakeholders, and other participants to explore all the details that the card doesn’t contain;

The confirmation is often a formal agreement on a solution that resulted from the “conversation." The above-mentioned solution should have acceptance criteria and must pass it successfully;

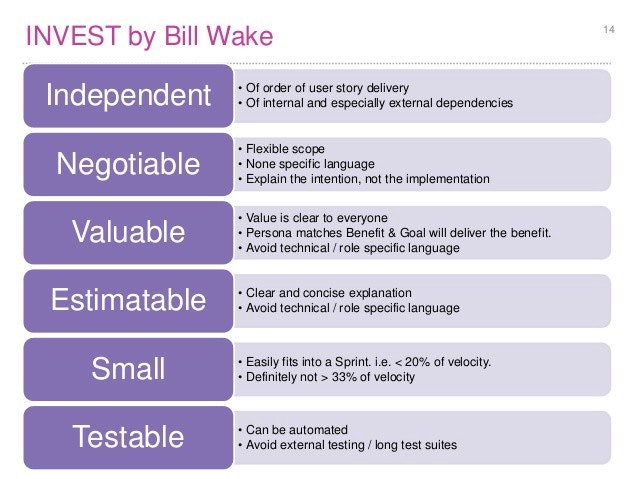

INVEST

The INVEST acronym is an important set of criteria that allows us to assess the quality of a user story. If a story fails to meet one of them, it should be rewritten or reworded.

INVEST stands for:

Independent—user stories shouldn’t overlap. A team should be able to work with one individual story at a time so that it can prioritize them in any particular order it sees fit;

Negotiable—stories shouldn’t be extremely detailed. On the contrary, they should be indicative of the conversation that needs to be had but shouldn’t prescribe a rigid solution. User stories should leave a fair amount of wiggle room, allowing the team to execute the story in a way it considers feasible;

Valuable (or vertical)—a story should provide users with evident value. If a story can’t be formulated with user value in mind, it should be rewritten or deprioritized;

Estimatable—a story should be worded in a way that would allow you to understand the size of the task at hand;

Small—a story should fit into an iteration;

Testable—in order to assess whether a story has been successfully addressed, there should be a set of evident criteria for its validation. These criteria should be testable and objective;

Who writes user stories?

It’s customary for product owners or product managers to be responsible for writing user stories. However, in our experience, UI/UX designers and UX researchers especially should be involved in the process as often as possible since all of these specialists can provide user stories with invaluable context.

Conclusion

To conclude, it’s safe to say that user stories are an invaluable tool in any designer’s arsenal. They keep the entire team focused on a clear goal, they make collaboration more comfortable and intuitive, and, most importantly, they revolve around our users’ needs.

![User Stories 101 [With Examples]](https://www.datocms-assets.com/16499/1625554924-user-stories-min-1.png?auto=format&dpr=0.84&fit=max&w=1920)